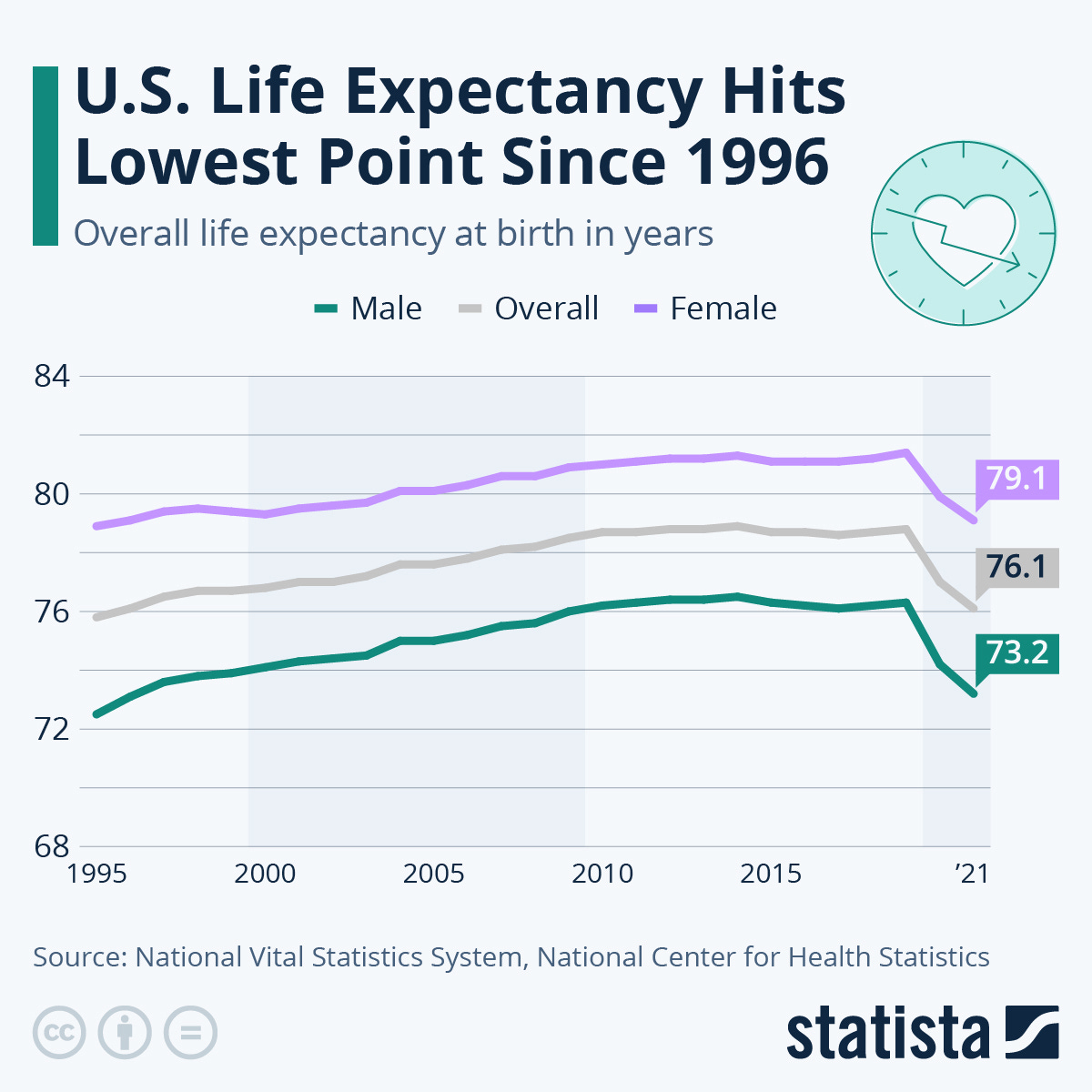

The 3 Big Lessons From America’s Declining Life Expectancy.

The life expectancy of an American boy is four years less than that of a European boy.

Longevity is probably one of the most obvious signs of social progress. The increase in life expectancy can legitimately be considered a cumulative victory. The victory of solidarity over social fatality allows the most fragile to take care of themselves and survive. The victory of science over grandmother's remedies. The victory of physical and health …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sylvain Saurel’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.