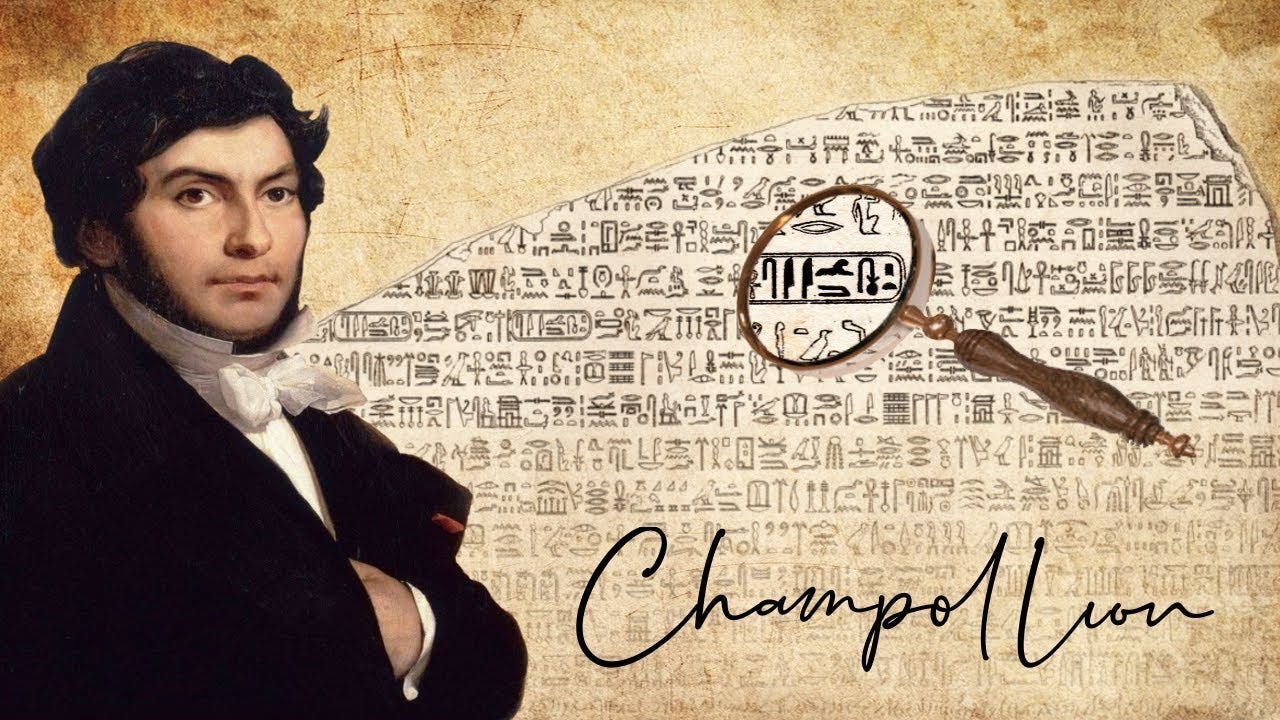

Champollion and the Mystery of the Hieroglyphs – In 1822, This Gifted Man Deciphered the Writing of the Pharaohs.

An achievement after hundreds of years of scientific trial and error.

In science, some formulas pass to posterity after a brilliant discovery. There is that of Archimedes for his thrust (“Eureka!”) but also that of Jean-François Champollion who, while piercing the mystery of hieroglyphs on September 14, 1822, would have hastened to announce the news to his brother Jacques-Joseph in these terms: “I believe that I hold my b…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sylvain Saurel’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.