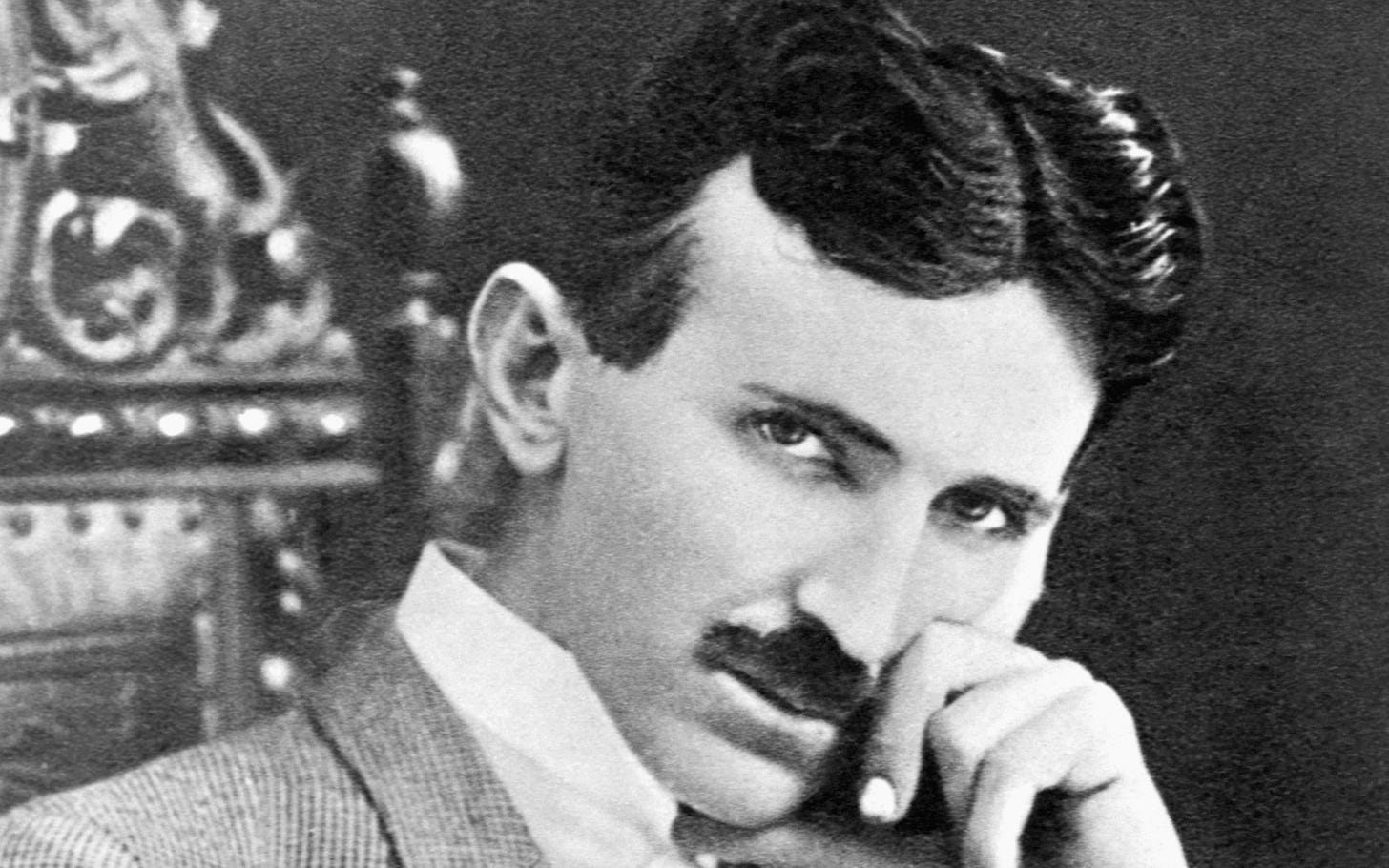

AC or DC? How Nikola Tesla Enabled George Westinghouse to Win the War of Electric Currents Against Thomas Edison.

Westinghouse won the no-holds-barred battle to electrify America.

The smoke rises under each of the legs of the animal wearing copper soles. A few seconds later, the enormous mass staggered, tilted, and collapsed. In front of Thomas Edison's camera, on January 4, 1903, the elephant Topsy, guilty of having killed a man, died, crossed by an alternating current of 6,000 volts.

What prompted Edison to immortalize the circu…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sylvain Saurel’s Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.